Origins of Human-Centered Design

A few years ago, I published an academic paper – which proved to be one of my most-read articles, on user-centered vs. human-centered design. In that paper, I compared the typical analytic methods and tools for user-centered design to an idea of human-centered design that came out of the field industrial engineering. Having seen the recent explosion of “user-centered” design fields such as User Experience design, I feel even more strongly that human-centered design is a discipline that has not yet fulfilled its potential for changes to the way in which we design technology systems for both work and play.

Human-centered design ideas come out of an emancipatory labor movement – originally in the UK – that looked at the constraints imposed by technology on work and focused on the impact of design on the quality of working life. This “socio-technical” approach to design (Emery & Trist, 1960) originated in studies of industrial processes, often embedded in the rapid societal and technical change of post World War II Britain conducted by researchers from The Tavistock Institute of Human Relations in London. A research team led by Eric Trist, Ken Bamforth, and Fred Emery studied the organization of coal-mining teams for various types of mine and coal-seam environment, concluding that the design of working arrangements and the use of technology needed to be balanced with the conditions in various type of working environment. They noted the tension between the need for miners to self-organize into collaborative groups that increased productivity by allowing miners autonomy in selecting their team role, and management directives which constrained group autonomy because this empowered the miners – and allowed them to negotiate the higher rates paid for skilled labor (Trist et al., 1963). They coined the term “sociotechnical” to define an approach to the design of working arrangements that balanced the socially-situated needs of human workers with the use of machinery to automate repetitive and dangerous work.

The ideas behind socio-technical design really took off in the 1980s, with the explosion of affordable office technologies and personal computing. Some notable thinkers in this aspect of design include:

Mike Cooley (Architect or Bee?, 2016), who explained how technology design choices exerted control over the labor force at the expense of social good. A key element of his arguments was to explain how the combination of conceptual design ability with the practical ability to understand the context of practice across multiple domains – common in the renaissance – has given way to a “deep dive” specialization in one area or another. This separation of “planning” from “doing” leads to design problems, as designers cannot envision the context in which their design will be used and make stupid mistakes. It also excludes consideration of social good when making design choices. Technology decisions are made on the basis of manufacturing cost rather than long-term, environmental impact.

Ken Eason, who argued in his early work (e.g. Eason, 1982) that designers’ choice of design approach affected system usability: a technology-led approach leads to ‘fire fighting’ when negative organizational effects become apparent; and user involvement in design tends to fail as users take longer to understand new technology than developers, so design is complete by the time they are able to make a contribution. He proposed an evolutionary design process that builds slowly from small-scale systems to large ones, retaining the flexibility to change and adapt to emerging user needs, promoting user learning via system prototypes and training, and involving users in system evaluation. His later work discusses how the typical “closed system” approach to IT design (goal-oriented and focused on predefined requirements) constrains the “open system” approach to design needed to balance the emergent needs of human users with technology goals, and also cater for the evolving system requirements engendered by changing global business environments (Eason, 2009).

Howard Rosenbrock (1981, 1988), was a visionary engineering theorist, who not only developed innovative techniques approaches to algorithm design for control engineering, but also saw engineering as an “art” (Rosenbrock 1988) that needed to balance the design of technology with the social needs, personal experience, and judgment of human beings. The opening to his 1981 paper, Engineers And The Work That People Do, contains the most chilling description of a work environment that I have ever read:

The plant was almost completely automatic. Parts of the glass envelope, for example, were sealed together without any human intervention. Here and there, however, were tasks which the designer had failed to automate, and workers were employed, mostly women and mostly middle-aged. One picked up each glass envelope as it arrived, inspected it for flaws, and replaced it if it was satisfactory, once every four-and one-half seconds. Another picked out a short length of aluminum wire from a box with tweezers, holding it by one end. Then she inserted it delicately inside a coil which would vaporize it to produce the reflector, repeating this again every four-and-one-half seconds. Because of the noise, and the isolation of the work places, and the concentration demanded by some of them, conversation was hardly possible.

Rosenbrock, H. H. (1981). Engineers And The Work That People Do, pg. 4.

This description still sends shivers down my spine. Not just because of the working conditions, but because of the casual way in which Rosenbrock mentions that the few manual work-processes on the light-bulb factory floor are not automated only because they are too complex or expensive to automate. They used human-beings for repetitive, demeaning jobs in which the environment made it too difficult to socialize with others, simply because they were cheaper or easier than designing an automated solution.

Moving to Participative Design

Obviously, any blog post cannot capture the whole of the socio-technical movement, with all the complexities that the various studies introduced. Here, I have tried to outline the tip of the iceberg, explaining the motivations that led to the HCI, CSCW, and agile design fields that influence contemporary design. But I cannot leave this discussion before mentioning the key influence of End Mumford. Professor Mumford was critical in promoting the importance of user participation in design (Mumford, 1983). She even conducted studies to demonstrate how users “went native” when participating in technology design, as technology-design skills were considered so glamorous and career-enhancing (1975). She devised a method – the ETHICS approach – that illustrated how to analyze requirements in ways that both balanced the technical and the social aspects of design, but also managed the inevitable subversion of social (work-system) design by considerations of technical expediency and optimization (Mumford & Weir, 1979; Mumford, 1995).

So how do we design human-centered systems that support workers in the work they need to do, while allowing them autonomy in the way that they do this work? The process devised over many years is to use socio-technical systems design.

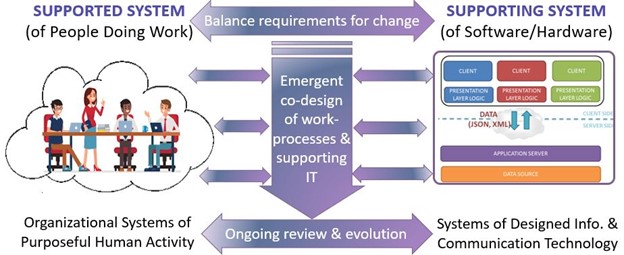

Figure 1. Socio-Technical Systems Design

As shown in Figure 1, above, socio-technical design balances the needs of a “supported system” of people doing work – a.k.a. the social system, with a “supporting system of information and communication technology – a.k.a. the technical system. It is important to start with the social system: the people who do the work are unfailingly the people who understand best what it requires, in the way of information and computing support. It is also important to see the drivers of design as the need to balance changes to the two systems, so the IT system supports the system of work (and not vice-versa). I refer to this principle as the co-design of business-process and IT systems. This concept is actually taken from the work of Peter Checkland, who argues that designed IT systems often solve the wrong problem, because designers fails to appreciate that the point of design is to support purposeful systems of human activity, rather than pursuing the separate aims of a technology architecture, data structures and information systems (Checkland, 1981; Winter, Brown, & Checkland, 1995).

References

Checkland, P. (1981) Systems Thinking, Systems Practice, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester.

Cooley, Mike (2016). Architect or Bee? The Human Price of Technology. UK: Spokesman Books. ISBN978-0-85124-8493.

Eason, K. D. (1982). The Process Of Introducing Information Technology. Behaviour and Information Technology, 1(2), April-June 1982>

Reprinted as Eason, K.D. (1984) “Managing Technological Change,” in Rob Paton, Suzanne Brown, Jake Chapman, Mike Floyd and John Hamwee (Eds.) Organizations: Cases, Issues, Concepts. The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK.

Eason, K. D. (2009). Before the Internet: The Relevance of SocioTechnical Systems Theory to Emerging Forms of Virtual Organisation. International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development, 1(2).

Emery, F. E., & Trist, E. L. (1960). Socio-Technical Systems. In C. W. Churchman & M. Verhulst (Eds.), Management Science Models and Techniques (Vol. 2). Oxford UK: Pergamon Press.

Mumford, E. & Sackman, H. (1975) Human Choice and Computers, North-Holland Publishing Company.

Mumford, E. & Weir, M. (1979), “Computer Systems in Work Design: the ETHICS Method”, John Wiley, New York

Mumford, E. (1983) Designing Participatively: A Participative Approach to Computer Systems Design. Manchester Business School, Manchester, UK.

Mumford, E. (1995) Effective Systems Design and Requirements Analysis: The ETHICS Approach. Macmillan, Basingstoke, UK

Rosenbrock, H. H. (1981). Engineers And The Work That People Do. IEEE Control Systems Magazine, 1(3), 4-8.

Rosenbrock, H. H. (1988). Engineering As An Art. AI & Society, 2(4), 315-320.

Trist, E., Higgin, G., Murray, H., and Pollock, A. B. (1963) Organisational Choice. London: Tavistock Publications.

Trist, E. L. (1981). The evolution of socio-technical systems. Toronto: Ontario Quality of Working Life Centre. Report access is provided courtesy of Larry Miller’s Blog on Leadership, Learning and Culture.

Winter, M. C., Brown, D. H., & Checkland, P. B. (1995). A Role For Soft Systems Methodology in Information Systems Development. European Journal of Information Systems, 4(3), 130-142.